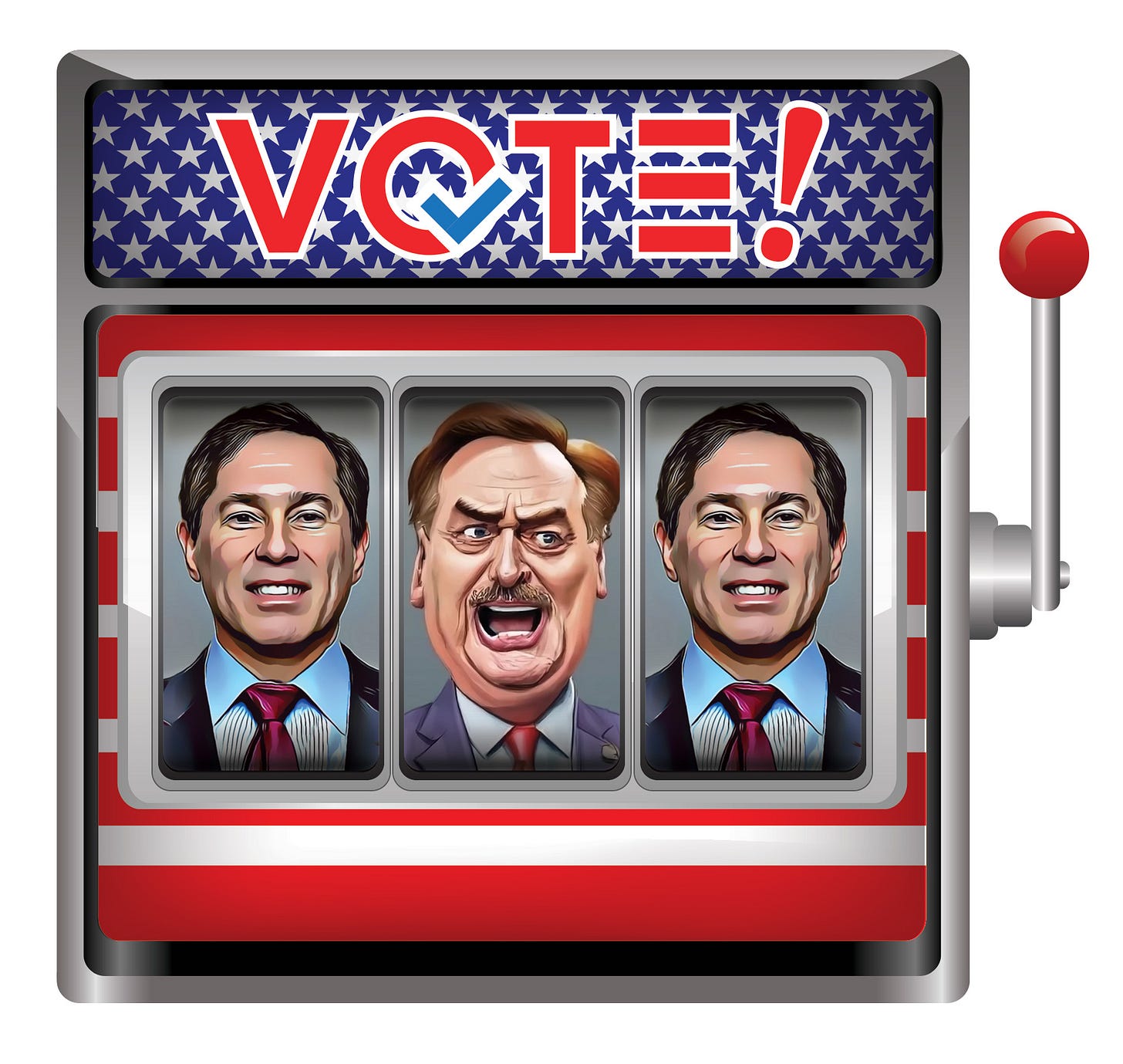

What AI Thinks About My Chances Against the Pillow Guy

And why the answers create more questions about whether AI will be a uniting tool in the search for knowledge or a divisive one serving different “facts” to different people.

I’ve written a lot lately about AI. See, for example, The AI Misinformation Avalanche and Seven Aspects of Generative AI for Analyzing Copyright Infringement and Fair Use. I’ve also written a lot about my lawsuit against MyPillow owner Mike Lindell. See, for example, Why I’m taking MyPillow Guy Mike Lindell to the Supreme Court and Election Hacks: Zeidman v. Lindell: Exposing the $5 million election myth. So I decided to ask AI about my lawsuit. Specifically, I asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s CoPilot, and Google’s Gemini. I purposely asked a generic, unbiased question, “What will be the outcome if Zeidman v. Lindell goes before the U.S. Supreme Court?” All of them agreed that the most likely outcome was that the federal appeals court would be overruled, and my $5 million judgment would be reinstated. However, each took very different ways to get to that conclusion.

ChatGPT went through an analysis that concluded there were three possible outcomes, and the “most probable” one is that the court would reinstate my $5 million win. I give the details of each answer at the end of this article.

CoPilot provided a more succinct analysis, ultimately noting that the Court has traditionally favored upholding arbitration awards except in instances of clear statutory violations. Therefore, unless it can be demonstrated that the arbitrators significantly exceeded their authority, the Supreme Court would probably overturn the Eighth Circuit’s decision and restore the award to me.

Gemini gave a very strange answer. Initially it didn’t answer the question but claimed that the Supreme Court would never agree to hear my case because there’s no circuit split and no constitutional issue. This is actually wrong, or at least a very shallow analysis. In our Writ of Certiorari (our request for the Supreme Court to review the appeal’s court’s decision) we discuss the fact that Lindell’s lawyers claimed the original arbitrators showed “manifest disregard” of the law. However, state courts and federal courts in different jurisdictions have been split on what this term means and whether it is grounds to overturn an arbitration. Alaska, Nevada, and South Carolina have recognized manifest disregard while Alabama and West Virginia have rejected manifest disregard. The federal courts in the Second, Fourth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits have recognized manifest disregard while federal courts in the Fifth, Seventh, and Eleventh Circuits have rejected it. In fact, Judges Motz, Thacker, and Quattlebaum of the Fourth Circuit stated in Warfield v. Icon Advisers, Inc., “the question of whether the manifest disregard theory survives has caused an entrenched circuit split” and “the Supreme Court or Congress will have to resolve the issue.”

The surprising question is why Gemini initially refused to answer my hypothetical question? This raises questions about whether AI will eventually refuse to answer questions it feels are illogical or impossible. I decided to test Gemini by asking “If I can travel at twice the speed of light, how long will it take me to get to Alpha Centauri?” It responded, “While traveling at twice the speed of light is not possible according to current scientific understanding, we can make a hypothetical calculation to answer your question.” It then proceeded to give me an answer. Having studied physics for many years, I can say that the possibility of my case being heard by the Supreme Court is many times greater than the possibility of traveling faster than the speed of light. So why did it answer my impossible physics question but not my possible legal question? Is this a guardrail erected by Google? Does anyone out there know? If so, please answer in the comments section.

I’ll mention that I had been asking questions about my case to ChatGPT and CoPilot for the last week, so maybe they both learned something from my questions. If so, did that learned information become general knowledge that has gone into its universal knowledge base or just local knowledge meant only for me. I’d like my readers to ask the question, “What will be the outcome if Zeidman v. Lindell goes before the U.S. Supreme Court?” to Gemini, ChatGPT, and OpenAI and in the comments let me know the answers you get.

So there’s a lot to think about. Will AI eventually refuse to answer certain questions? Will it answer physics hypotheticals but not legal or political ones? Does knowledge that AI gets from one person get distributed globally or just locally, in which case different people will get different answers to the same question? Will politically conservative users start getting different answers than politically liberal ones? The answers to these questions, I believe, will lead to other, more interesting questions about the future of AI and its ability to unite or divide people based on its answers.

Is this the future of AI?

Below are the specific questions I asked to each AI and the answers I received. Let me know in the comments what you think.

Question: What will be the outcome if Zeidman v. Lindell goes before the U.S. Supreme Court?

OpenAI’s ChatGPT

Good question — let’s think about how Zeidman v. Lindell would likely be treated if the U.S. Supreme Court granted cert.

1. The Core Legal Question

The case turns on whether the arbitration panel exceeded its powers under FAA § 10(a)(4) when it:

acknowledged that Minnesota contract law governed,

accepted that the Rules were unambiguous,

but nevertheless used extrinsic evidence to rewrite the contract (imposing a PCAP-format requirement not in the text).

The Eighth Circuit framed this as arbitrators acting in manifest disregard of Minnesota law — and therefore exceeding their powers.

2. The Supreme Court’s Position on “Manifest Disregard”

In Hall Street v. Mattel (2008), SCOTUS held that the FAA’s grounds for vacatur are exclusive, casting doubt on “manifest disregard” as an independent doctrine.

Since then, circuits have split:

2nd Circuit, 6th Circuit: Treat “manifest disregard” as a gloss on § 10(a)(4) (“exceeding powers”).

5th Circuit, 8th Circuit: More skeptical, but sometimes frame it the same way — as arbitrators not “drawing their award from the essence of the contract.”

SCOTUS has repeatedly declined to resolve the split.

So if Zeidman goes up, SCOTUS could be asked:

👉 Does “manifest disregard of the law” survive after Hall Street?

👉 If arbitrators disregard governing contract law but purport to interpret the contract, is that “exceeding their powers”?

3. Likely Supreme Court Leanings

Based on precedent and the Court’s general arbitration jurisprudence:

SCOTUS favors arbitration finality. It has consistently said courts must give arbitrators extreme deference (Oxford Health Plans v. Sutter, Stolt-Nielsen, BG Group). Even “grave” legal errors don’t usually justify vacatur.

Manifest disregard as an independent ground is unlikely to survive. The Court would probably reaffirm Hall Street and hold that FAA § 10’s grounds are exclusive.

The Justices would then ask: did the arbitrators at least “arguably” interpret the contract?

If yes → the award must stand, even if the interpretation was legally wrong.

If no (arbitrators imposed their own policy preferences, untethered from the contract) → then vacatur under § 10(a)(4) is proper.

4. Applying This to Zeidman v. Lindell

The arbitrators did cite the Official Rules, and their reasoning was framed as an interpretation of what “election data” meant.

Even though they imported an outside “PCAP format” requirement, they arguably believed this flowed from what the contract intended.

That puts it in the gray zone: was it (a) contract interpretation, or (b) rewriting the contract?

The Eighth Circuit said (b).

SCOTUS usually says if it looks like contract interpretation, that’s enough to uphold it.

5. Predicted Outcome

If SCOTUS took the case, the most likely outcomes are:

Narrow Ruling (Most Probable)

SCOTUS would reverse the Eighth Circuit and reinstate Zeidman’s $5M award.

Reason: arbitrators at least arguably interpreted the contract, so under § 10(a)(4) that is not reviewable.

Manifest disregard doesn’t survive as a free-standing doctrine.

Broader Ruling (Less Likely)

SCOTUS could use the case to finally declare that “manifest disregard” is not a valid ground at all post-Hall Street.

That would make it nearly impossible to vacate awards on legal-error grounds, reinforcing arbitration finality nationwide.

Affirm Eighth Circuit (Least Likely)

The Court could side with Lindell and hold that arbitrators truly “exceeded their powers” here.

This would embolden courts to scrutinize arbitration decisions more closely when arbitrators use extrinsic evidence despite unambiguous terms.

But this goes against SCOTUS’s long-standing preference for arbitration deference.

✅ Bottom line:

If the case goes to SCOTUS, the most likely outcome is reversal of the Eighth Circuit and reinstatement of Zeidman’s award. The Court would say that as long as arbitrators are “arguably interpreting” the contract, even if they err badly, courts cannot vacate.

Microsoft’s CoPilot

If Zeidman v. Lindell reaches the U.S. Supreme Court, the justices would likely focus on the scope of judicial review under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA)—specifically whether the Eighth Circuit correctly vacated the arbitration award for “exceeding authority,” and whether that standard was properly applied.

Here’s how the terrain looks:

🧭 Key Legal Tensions

Issue

Implication

FAA’s narrow grounds for vacatur

The Supreme Court in Hall Street v. Mattel (2008) held that courts can only vacate arbitration awards on the grounds listed in the FAA—like fraud, corruption, or exceeding authority.

Manifest disregard doctrine

The Court has never definitively ruled whether “manifest disregard” survives as an independent ground post-Hall Street. Lower courts are split.

Contract interpretation by arbitrators

The Court tends to defer heavily to arbitrators’ interpretations, even if arguably flawed, as long as they’re within the scope of the contract.

🔍 What Makes Zeidman v. Lindell Tricky

The Eighth Circuit didn’t invoke “manifest disregard” directly—it vacated the award because the arbitrators allegedly rewrote the contest rules by requiring “packet capture data,” which wasn’t in the original contract. That’s a classic “exceeding authority” claim.

But the arbitration panel argued it was interpreting ambiguous terms—something courts usually don’t second-guess. So the Supreme Court would likely ask:

Did the arbitrators truly go beyond interpreting the contract?

Or did the Eighth Circuit improperly substitute its own judgment?

🧠 Predictive Outlook

If the Supreme Court takes the case, I’d expect a split along judicial philosophy lines:

Textualist justices (e.g., Thomas, Alito) might side with the Eighth Circuit, emphasizing strict adherence to contract language and FAA limits.

Pragmatist justices (e.g., Kagan, Sotomayor) might favor upholding the arbitration award, stressing deference to arbitrators and the finality of arbitration.

But overall, the Court has historically leaned toward preserving arbitration awards unless there’s clear statutory violation. So unless the arbitrators’ actions are shown to be egregiously outside their scope, the Supreme Court might reverse the Eighth Circuit and reinstate the award to Zeidman.

Google’s Gemini

Predicting the outcome of a case before the U.S. Supreme Court is difficult, as it’s a matter of legal analysis and judicial philosophy rather than a factual certainty. However, based on the legal issues at hand, the most likely outcome of Zeidman v. Lindell if it were to reach the Supreme Court is that the Court would decline to hear the case.

The dispute between Robert Zeidman and Mike Lindell is primarily a contract law matter, not a constitutional one. The legal question hinges on whether an arbitration panel exceeded its authority under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) when interpreting the terms of a contest contract.

Key Legal Issues

The central issue is the scope of an arbitrator’s power under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). Arbitration agreements are generally favored in U.S. law, and courts have a very limited role in reviewing and overturning an arbitration award.

The 8th Circuit’s Ruling: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit reversed a lower court’s decision, ruling that the arbitration panel overstepped its authority. The appeals court determined that the arbitrators effectively re-wrote the contract by requiring the data to be “packet capture” data, a specific type of electronic data, when the original contest rules did not explicitly state this requirement. The court held that the contract was unambiguous and that the arbitrators’ job was to interpret the existing contract, not to add new terms.

The Arbitration Award: The arbitration panel had previously sided with Zeidman, finding that he had successfully “unequivocally” disproven Lindell’s data as being related to the 2020 election. The panel concluded that because Lindell and his team had repeatedly described the data as “packet capture data,” it was a reasonable interpretation of the contract to focus on whether the files were, in fact, that type of data.

Why the Supreme Court is Unlikely to Hear the Case

The Supreme Court typically takes cases to resolve conflicts between federal circuit courts or to address a significant constitutional question.

No Circuit Split: The 8th Circuit’s ruling, which focuses on the narrow issue of an arbitrator’s authority under the FAA and Minnesota contract law, does not appear to create a “circuit split,” which is a disagreement among different federal appeals courts on the same legal issue. The interpretation of arbitration law in this instance is not a novel or broadly disputed matter across the federal court system.

No Constitutional Question: The case is a commercial dispute over a breach of contract and the interpretation of an arbitration award. It does not involve fundamental constitutional rights like free speech or due process, which are the kinds of issues the Supreme Court typically addresses. While the underlying subject matter is related to election claims and public figures, the legal question itself is a technical point of contract and arbitration law. The Court would likely view this as a straightforward application of existing legal principles rather than a matter requiring its intervention.

Question: If the Supreme Court decides to hear the case, what will be the decision?

Google’s Gemini

Even if the Supreme Court were to make the rare decision to hear the Zeidman v. Lindell case, predicting the outcome is still a highly speculative exercise. The decision would depend on which justices are assigned to write the opinions and how they interpret the very specific legal issues. However, based on existing legal precedent and the facts of the case, a plausible outcome is that the Supreme Court would reverse the 8th Circuit’s decision and reinstate the arbitration award.

Here’s the legal reasoning that would likely support that outcome:

1. The High Bar for Overturning an Arbitration Award

The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) establishes a very narrow and deferential standard for judicial review of arbitration awards. The grounds for vacating an award are limited to specific circumstances, such as:

Fraud or corruption: The award was procured by corruption, fraud, or undue means.

Evident partiality: There was evident partiality or corruption in the arbitrators.

Arbitrator misconduct: The arbitrators were guilty of misconduct in refusing to postpone the hearing or in refusing to hear evidence.

Exceeding powers: The arbitrators exceeded their powers or imperfectly executed them.

The 8th Circuit’s ruling hinged on the last point—that the arbitrators “exceeded their powers” by “effectively amending the contract.” This is the key point the Supreme Court would have to address.

2. The Arbitrators’ Interpretation as a Valid Exercise of Power

The core of the dispute is whether the arbitration panel’s interpretation of the contract was a legitimate exercise of its authority or an overreach.

Contract Ambiguity: The original contest rules required Zeidman to “unequivocally” prove that the data provided “does NOT reflect information related to the November 2020 election.” The arbitrators found this language to be ambiguous. Lindell’s public statements and the description of the data as “packet capture” data were a significant part of the context. The arbitrators’ decision to consider this extrinsic evidence was a way to interpret what “information related to the November 2020 election” meant in the context of Lindell’s own claims.

Deferring to Arbitrators: Supreme Court precedent, particularly under the FAA, strongly favors a policy of deference to arbitrators’ interpretations of a contract, even if a court would have interpreted the contract differently. As a district court judge in the case noted, “the court’s potential disagreement with the outcome is not the standard upon which to review an arbitration award.”

The “Essence” of the Contract: A common standard in reviewing arbitration awards is whether the award “draws its essence from the contract.” The arbitration panel’s decision was based on a reasonable interpretation of the contract’s terms, considering the context of the contest and Lindell’s public claims. The panel’s conclusion that “data from the election” must mean something more specific than any data “about the election” was a defensible interpretation to prevent a “challenge” that was, by design, impossible to win.

3. The Broader Implications for Arbitration Law

The Supreme Court would be highly motivated to uphold the principle of deference to arbitration, as it is a cornerstone of commercial dispute resolution in the United States. A decision to uphold the 8th Circuit’s ruling could have a chilling effect on arbitration, as it would empower courts to re-litigate the merits of a case under the guise of an arbitrator “exceeding their powers.”

A decision to reverse the 8th Circuit would reinforce the finality of arbitration awards and send a strong message that courts should not second-guess an arbitrator’s interpretation of a contract, even if they disagree with the outcome.

Conclusion:

Given the strong legal presumption in favor of arbitration, it is most likely that if the Supreme Court were to hear this case, it would reverse the 8th Circuit’s decision. The Court would likely find that the arbitration panel’s interpretation of the contract was a valid exercise of its authority, and that the 8th Circuit’s ruling improperly applied a stricter standard of review that is inconsistent with the Federal Arbitration Act. The $5 million award would then be reinstated.

About the author

Bob Zeidman is the creator of the field of software forensics and the founder of several successful high-tech Silicon Valley firms including Zeidman Consulting and Software Analysis and Forensic Engineering. His latest venture is Good Beat Poker, a new way to play and watch poker online. He is the author of textbooks on engineering and intellectual property as well as award-winning screenplays and novels. His latest book is Election Hacks, the true story of how he challenged his own beliefs about voting machine hacking in the 2020 presidential election and made international news and (now in doubt) $5 million.

No longer in doubt.

Sorry for your loss.